Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | TuneIn | RSS

The book

Buy the new textbook (Bryan edited, Brandon authored a chapter) here or on Amazon:

Concepts in Surgical Critical Care, First Edition

ed. Bryan Boling, DNP, ACNP; Kevin Hatton, MD, FCCM; Tonja Hartjes, DNP, ACNP-BC, CCRN, FAANP

The podcast

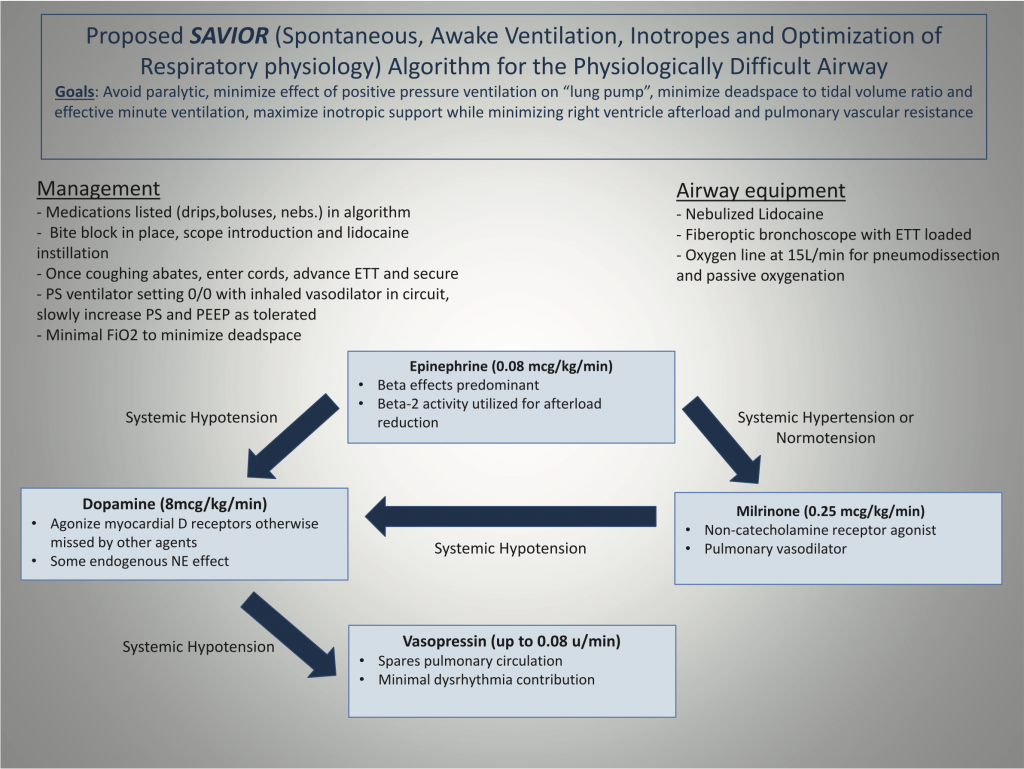

An in-depth look at the management of right heart failure, with a focus on preserving peri-intubation hemodynamics using the SAVIOR protocol—featuring its co-creator, anesthesiologist and intensivist from the University of Kentucky, Habib Srour.

Takeaway lessons

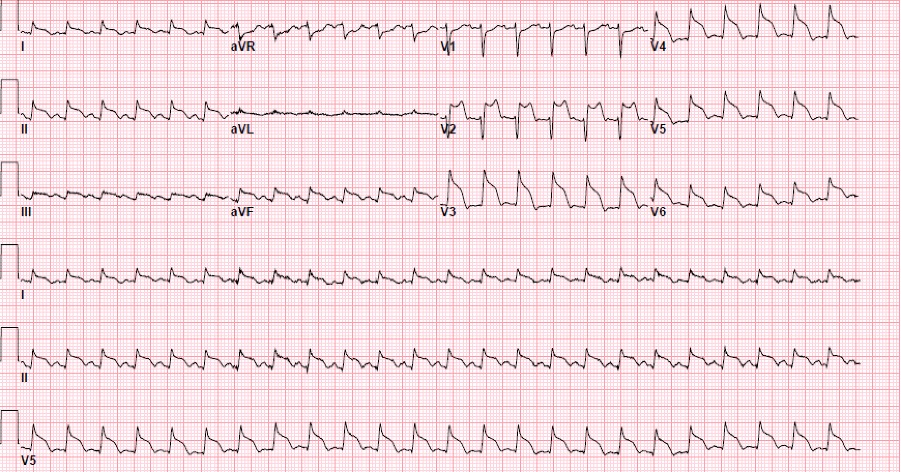

- When facing undifferentiated shock and a complex picture, look for one point of data to help distinguish the etiology. Try touching the feet: cold is a good indicator of a significant cardiogenic component.

- The flip side of hypoxic vasoconstriction is hyperoxic vasodilation of the pulmonary vasculature—i.e. an overly high FiO2 will tend to worsen V/Q matching.

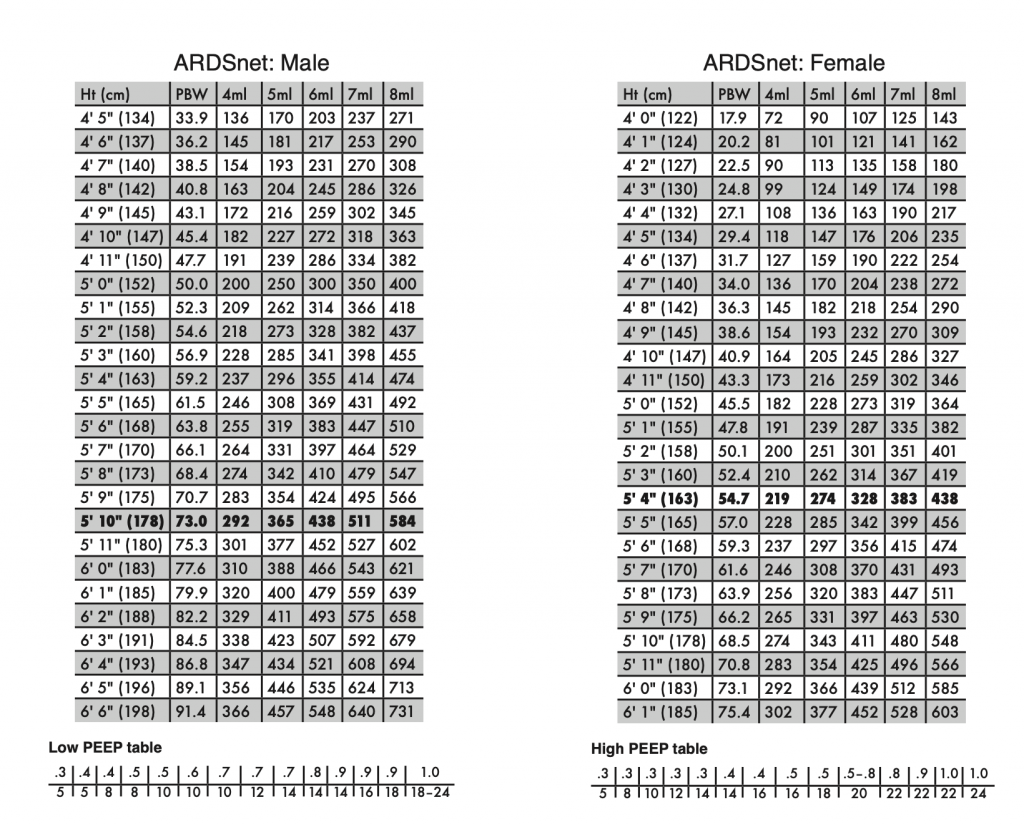

- To hemodynamically manage RV failure without worsening RV afterload, consider the Rule of 8s cocktail:

- Epinephrine .08 mcg/kg/min

- Dopamine 8 mcg/kg/min

- Vasopressin .08 units/min

- Inhaled epoprostenol (Veletri/Flolan) 8 ml/hr

- The “lung pump” of negative pressure respiration provides a substantial amount of cardiac output, particularly in the setting of RV failure. Paralysis, sedation, and intubation removes this. The period of apnea also worsens acidosis which increases PVR.

- The dead space to tidal volume ratio increases by at least 50% after intubation; it will be impossible to match an already-high spontaneous minute ventilation on the ventilator.

Resources

References

- Srour H, Shy J, Klinger Z, Kolodziej A, Hatton KW. Airway Management and Positive Pressure Ventilation in Severe Right Ventricular Failure: SAVIOR Algorithm. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34(1):305‐306. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2019.05.046