Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | TuneIn | RSS

The hows, whys, logistics, and applications of focused, bedside transesophageal echocardiography performed by critical care and EM providers, with Felipe Teran, assistant professor of emergency medicine at Weill Cornell and director of the Resuscitative TEE Project.

Takeaway lessons

- As a rule, resuscitative TEE is performed in patients with a secured airway.

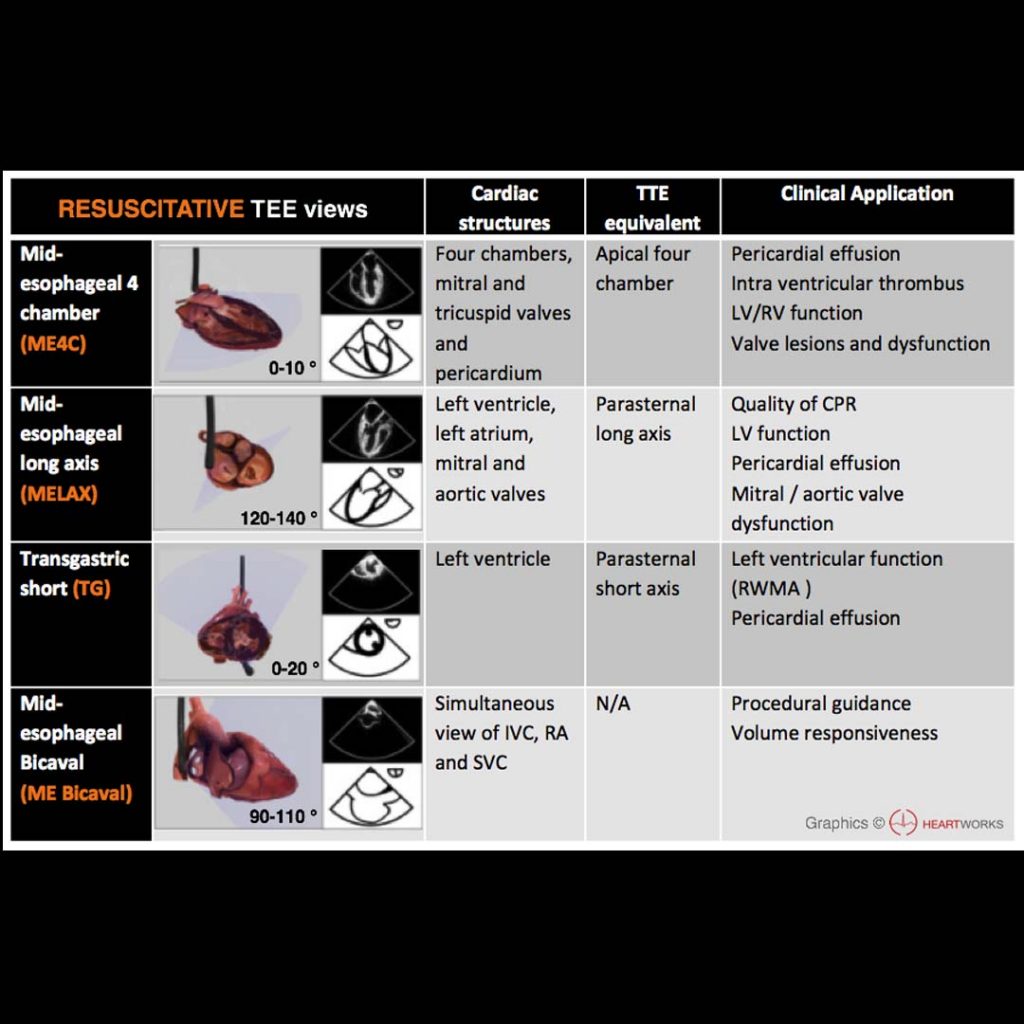

- TEE views are not unlike TTE views, just at a different angle (often backwards/upside down down). The technical skills are very similar, and skilled TTE users will find the learning curve short. There are actually fewer probe manipulations (in and out, left and right, and Omniplane rotation, along with some less-used ones like flexion/extension).

- The same questions you’d typically ask with TTE can be asked with TEE: is there tamponade? is there cardiogenic shock? is there RV failure? is there hypovolemia? These can be answered even in patients with technically-difficult surface windows.

- Some questions hard to answer with TTE can be answered with TEE, such as obtaining reliable RV inflow-outflow views and reliable valve assessments.

- Some new questions can be answered with TEE alone: is there aortic dissection? are catheters and wires (ECMO, Impella, pacing wires, etc) optimally placed?

- TEE has specific applications in cardiac arrest: are chest compressions optimally positioned on the chest? What is the rhythm? It provides monitoring much more continuous than intermittent TTEs, since it can be left in place.

- In an ideal world, resuscitative TEE would be handled very much like TTE, and performed in a similar way—not restricted to some small group of “superusers” or for very rare cases.

- When implemented by trained users in appropriately-selected cases (e.g. in shock with inadequate transthoracic windows), it impacts care virtually 100% of the time.