Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | TuneIn | RSS

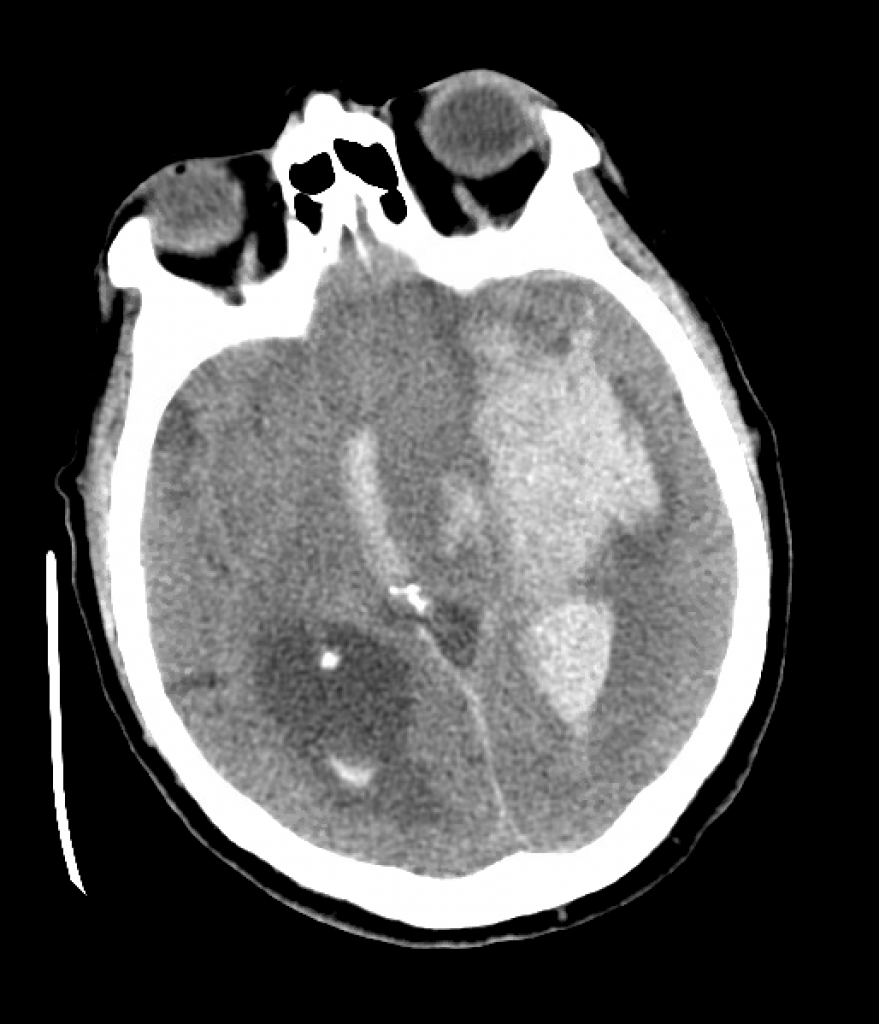

We review a case of massive intraparenchymal hemorrhage progressing to brain death, including the process of brain death testing and declaration, with Dr. Casey Albin (@CaseyAlbin), neurologist and neurointensivist, assistant professor of Neurology and Neurosurgery at Emory and part of the NeuroEmcrit team.

For 20% off the upcoming Resuscitative TEE courses (through July 23, 2022), listen to the show for a promo code for CCS listeners!

Takeaway lessons

- In general, in patients with good baseline function, it’s reasonable to be fairly aggressive with initial care, such as placement of intracranial pressure monitors, even if long-term goals of care are unclear—it can always be escalated.

- Although ICH score is associated with mortality, the original study allowed withdrawal of care at discretion of the clinicians, so the data may be tainted by self-fulfilling prophecy—withdrawal of care may lead to poor prognosis in some cases, not always the reverse.

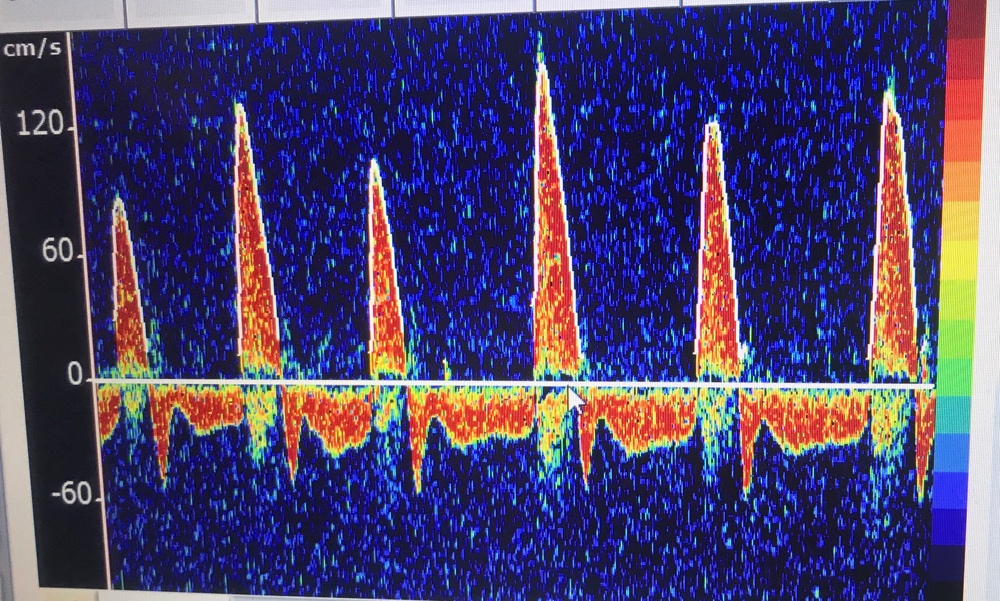

- Sodium goals are ideally titrated to ICP (with invasive monitoring). In its absence it’s best to target clinical findings, unless you have tools like TCDs or optic nerve sheath ultrasound, or just frequent CT scans. Arbitrary sodium goals are rarely helpful.

- There is good evidence for decompressive hemicraniectomy for large MCA infarct IF the patient is young; it is less clear in the elderly. If it’s going to be done, do it early.

- If herniation is clear via ICP or imaging, don’t spare sedation for the sake of a neuro exam, unless you’re at the point of stepping back and assessing for long-term futility and possible brain death.

- 4-5 days into admission is often when families begin to understand the nature of a devastating neurologic injury. In some cases, discussion of futility and brain death may be initiated by families after doing their own research.

- The first step is holding sedation and waiting ~5 half-lives for confounding drugs to clear; impaired renal or hepatic clearance should be taken into account here. (Pharmacy may be helpful.) Paralysis should be held and train-of-four can be used to confirm. Drug levels can be used to confirm clearance of opioids, etc if needed.

- The law (Uniform Declaration of Death Act) doesn’t always agree with guidelines (while hospital policies may differ even further). The UDDA requires complete brain death, whereas the AAN’s guidelines don’t necessarily require pituitary death (patient need not be in DI), but all do require more than just brainstem death—for example, a locked-in patient would not qualify.

- Expect and manage DI, as hypovolemia and hypernatremia may make the patient too unstable to tolerate brain death testing. Consider a vasopressin drip, replace volume, etc.

- As the chest wall becomes denervated, it loses elastic recoil, while hypovolemia may cause very hyperdynamic cardiac function. The combination can cause strong chest wall vibrations which may autotrigger the ventilator, often confusing staff and family who believe the patient is breathing spontaneously.

- Perform brain death testing in a systematic, scrupulous manner. Print your hospital policy and use it as a formal checklist. You’ll need a bright penlight, a tongue depressor or Yankhauer catheter, a Q-tip or gaue for corneal reflexes, 50 ml x2 of ice-cold water and a syringe with an IV catheter on the tip for cold calorics, and some kind of insufflation catheter or a T-piece for apnea testing.

- Pitfalls: remember to test corneals by touching the actual cornea, not the sclera. Cold calorics are performed by irrigating the ear canal and watching for gaze deviation (any deviation shows brainstem activity). Gag reflex must be checked all the way in the back of the oropharynx with vigorous stimulation. Cough and pain responses must also be checked with substantial stimulation. Warn family ahead of time about the possibility of purely reflexive triple flexion.

- Consider bringing the family to watch, which helps encourage transparency. Warn them ahead of time that if the test is confirmatory, it will indicate the patient is dead by brain criteria.

- You generally want an arterial line for the apnea test, and have vasopressors running and ready to maintain the SBP >100. Put the patient on 100% FiO2 and get a baseline ABG showing normocapnia and a PAO2 >200. (If the patient has a baseline elevated PACO2, follow your local policy.) Oxygenate the patient passively, such as by inserting an insufflation catheter hooked up to oxygen down the ET tube after disconnecting the ventilator. Uncover the patient’s chest and watch for chest rise.

- A confirmatory apnea test is one where the PACO2 rises by 20 points, without any clinical signs of breathing; hence the team needs to be in the room, physically observing the patient. An equivocal test is one where the test cannot be completed or the PCO2 fails to adequately rise to confirm adequate levels. Most tests are completed by 10 minutes, but start sending blood gasses earlier than that (e.g. at 6, 8, 10 minutes), as you may need to terminate the test due to instability while waiting for the most recent gas and you’ll want to know if the patient had finished.

- Confirmatory/ancillary tests can be done if the clinical and apnea tests cannot be done, or are not completely definitive due to confounding factors. They can include TCDs, nuclear flow studies, or EEG if specialized equipment and readers are available. Catheter-directed 4-vessel cerebral angiography is another option, but CTA/MRA are not. Most of these tests are looking for intracranial circulatory arrest, i.e. lack of blood flow to the brain—dead cells have no metabolic demand and shunt blood away.

- Perform brain death testing as soon as clinically appropriate; they only become more unstable.

Resources

As an intensivist, I love your podcasts. This episode is a really good scenario I deal with this daily. However, I felt like we’re missing a huge patient /family demographic here.

I have to ask Dr Albin what she would do if the pt stabilizes and remained anisocoric pupils and wants everything done. Trach and peg? What’s the long term prognosis for this particular case?

Family will ask, how long do we wait after trach and peg? “My family member is a fighter.” I wish those were addressed. Those are the true difficult cases.

Again, thank you for creating this content!

Hi there

Yes I totally agree with you! this is a really hard thing to counsel families through.

In my mind there are two patients populations — there is the under <60 crowd that I think can really surprise us in their functional recovery.. and then there are the older patients.

If I have a young patient who is herniating, that patient is getting max ICP treatment and going for a decompression with NSGY. Because these are patients that can with time achieve an mRS =< 3 (not perfect, but I think many patients feel like this is a reasonable QoL.). I actually just did a post on how the ICH score really overestimates mortality and even morbidity if patients are treated aggressively upfront. https://twitter.com/caseyalbin/status/1521958914450931715. that said, I always talk to families about how long the road is, how uncertain the recovery is, how there will be many set backs and before we commit to t&g and the long haul, I'll have them meet with social work to get a real look at the placement issues and the finances… this is REALLY expernsive care for patients… especially if they are underinsured or not insured.. I try to make sure that our team is transparent about the realities, although I personally don't have those conversations for obvious reasons. We do a ton of t&gs and see how things go. I think some people do ok and some people unfortunately don't, but I think it gives family peace to have more time.

Then, there are the older patients… a 75 yo who is herniating is just really unlikely to do well. If hydrocephalus is playing a role we are certainly willing to put in an EVD and try to see if we get any improvement with simple interventions… but we don't take these patients to decompressive surgery. this to me is a long GoC conversation of trying to be real about the reality that there is such a tiny maybe non-existent chance this person ever returns to an independent life. Sometimes you just look at the scan an know that if there isn't a surgical plan, no amount of 23% is going to fix it and I spend a lot of time with families about how this is a devastating catastrophe we don't have a solution for. Other times, its kinda borderline and we do push medical management and have a lot of family meetings about the likely long term outcome being poor. I don't know what the right answer is here. I have to say these are cases when it's hard for my personal biases about what constitutes a "meaningful" life to not color how I see things, I am still making peace with sometimes the right thing is trach/peg and more time even when I know that the mRS at 6 months looks horrific… I dunno. that kind of case is tough. I just try to remember that no one wants their loved one to suffer, the bar for what constitutes suffering is different for each family though…. Basically, I dont' have the right answer here.