Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | TuneIn | RSS

We discuss the nuts and bolts of urinary infection with an obstructing stone with Ashley Winter (@AshleyGWinter), board certified urologist with a fellowship in male and female sexual medicine, and chief medical officer of Odela Health.

Takeaway lessons

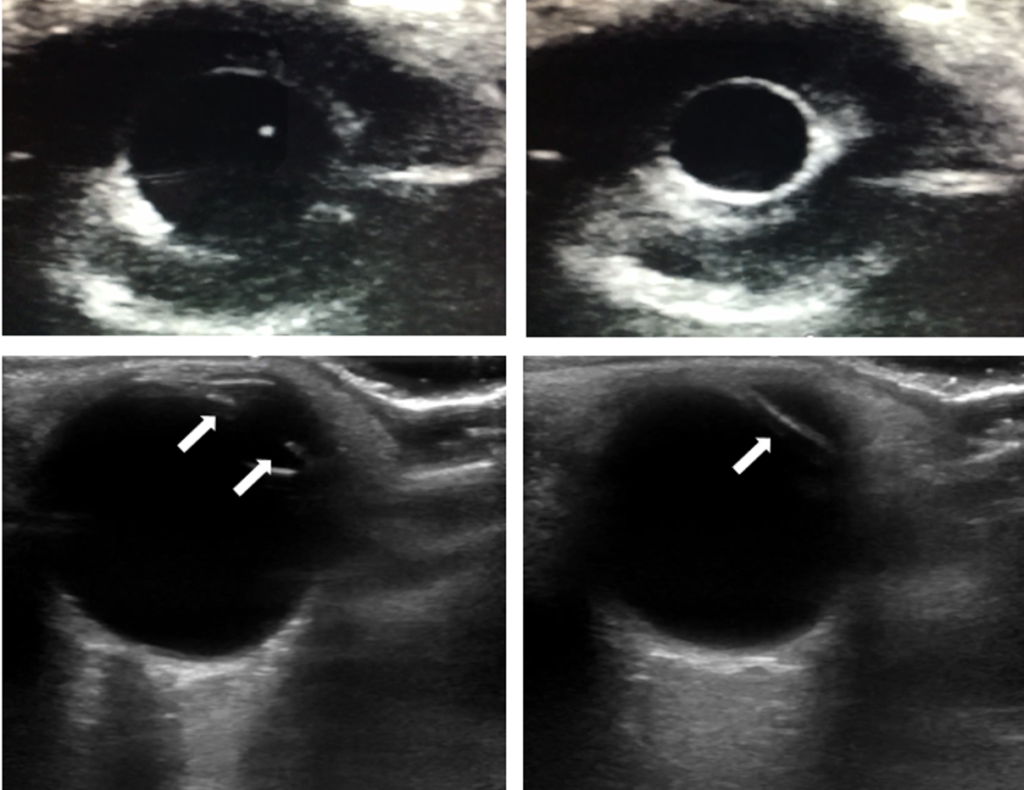

- A patient with UTI (or even just undifferentiated sepsis) and a non-trivial ureteral stone generally needs decompression of the affected kidney, whether or not there is significant hydronephrosis on imaging. Hydro is sensitive to other factors, such as dehydration, but its absence does not rule out sepsis secondary to urinary obstruction. CT is more sensitive here than ultrasound, which is mostly useful for ruling in hydronephrosis. (Such patients will usually need a stent, not a nephrostomy, as the latter is difficult when there is little hydronephrosis.) From a urology perspective, the size and position of the stone is probably more important than the hydronephrosis.

- That being said, be attuned to the possibility of a patient with another source of sepsis, and an incidental bacteriuria and kidney stone. Anesthesia and a urology procedure won’t help these people. A cleaner urinary sample (e.g. straight cath or Foley, if the initial sample was a “clean” catch) can sometimes help here.

- Consider also that a completely obstructing stone may be hiding pyelonephritis because the bacteria and leukocytes cannot pass the stone. This is not a very common scenario, but can lead to a “clean” urinalysis, so consider it in a patient with an obstructing stone and septic picture.

- Try to get a urine sample before giving antibiotics.

- Intra-renal stones will usually not cause obstruction, but occasionally in the setting of abnormal anatomy they may, such as a stone in a caliceal diverticulum causing a local/segmental hydronephrosis.

- Obstructing stone + UTI + unstable with sepsis = emergent decompression within hours. Overnight cases should generally be drained overnight. Stable patients can potentially wait longer.

- Option #1 for decompression is a ureteral stent, which stretches from the intra-renal pelvis to the bladder, traversing the area of the stone, and is deployed via cystoscopy. Urine drains around the stent, not necessarily through it. Stents can usually only be left for a maximum of 3 months and should be removed when no longer needed (i.e. when serial imaging shows passage of the stone, or a procedure has been performed to remove the stone). Long-term stent requirements involve serial stent replacements. They are placed in the OR under some level of sedation. Very distorted anatomy, such as in oncology cases, may make it difficult to find the ureteral orifice or to traverse the ureter.

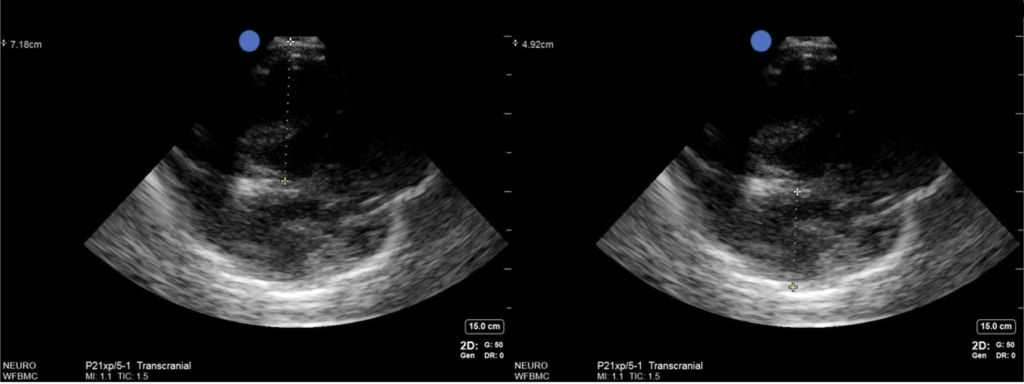

- Option #2 is a percutaneous nephrostomy. These are placed by Interventional Radiology. The patient is proned (not possible in all patients), and imaging (usually ultrasound) is used to guide a needle to the renal pelvis, then a pigtail catheter using a Seldinger technique. This can often be done with local anesthesia only. Lack of significant pelvic dilation or large body habitus make these more difficult. The result is a nephrostomy tube and drainage bag, which can be aesthetically unappealing to many patients. Anticoagulation may be a contraindication since you’re puncturing the renal parenchyma. They are usually not intended to be permanent, but can be left long-term in some cases.

- Stents tend to be more uncomfortable, sometimes creating flank pain or a sensation of the need to void even with an empty bladder. Urine can even reflux up the stent into the renal pelvis during voiding.

- Urostomies can sometimes make the procedure to remove a massive intrarenal stone like a staghorn calculus, since percutaneous nephrolithotomy can use the pigtail for access. Smaller stones can be removed via ureteroscopy.

- Some stones are impacted, which may be difficult to navigate across with a stent. Technical maneuvers can be attempted, but occasionally it can’t be done and nephrostomy needs to be done as a rescue.

- Ultimately, stent vs nephrostomy often comes down to institutional and logistical considerations, such as availability of urology compared to IR. Many centers have policies on who to call first.

- A common phenomenon is clinical deterioration after decompression. Some of this may be iatrogenic; both stenting and nephrostomy involve pressurizing the renal pelvis by injecting contrast, which can force out some bacteria into the circulation. Reducing the volume or rate of contrast injection may help with this.

- Antibiotic coverage can be as routine for sepsis, but if there is complex urological history, remember to check prior cultures (including stone cultures, if available), which may reveal a history of resistant organisms.

- Stented patients who fail to improve in the acute to subacute period may be experiencing stent migration. Check position with a plain x-ray (KUB); if the proximal portion is not curled, further imaging may be needed as it suggests it’s not in the kidney.

- Stent removal can sometimes precipitate instability as well if there is some degree of infection present.